Content from Data Management Plan (DMP) Overview

Last updated on 2024-04-01 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 28 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is a Data Management Plan (DMP)?

- When should a researcher make a DMP?

- What information should a DMP contain?

Objectives

- Name the components covered in a DMP

- Articulate the purpose(s) of a DMP

What is Data Management?

Data management is a broad term that encompasses collecting, storing, sorting, organizing and sharing data. We all use some form of data management in our lives: making to-do lists, putting paperwork in labeled file folders, organizing photos by trip name. For researchers, data management is an essential part of the research process that enables them to make sense of the vast amounts of data they collect. Data management practices strive to make data FAIR - Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. In other words, good data management makes it easy to find, understand, and reuse a specific piece of information again. It also enhances reproducibility by making it clear what data were used to support which conclusion, and increases security by keeping track of sensitive information.

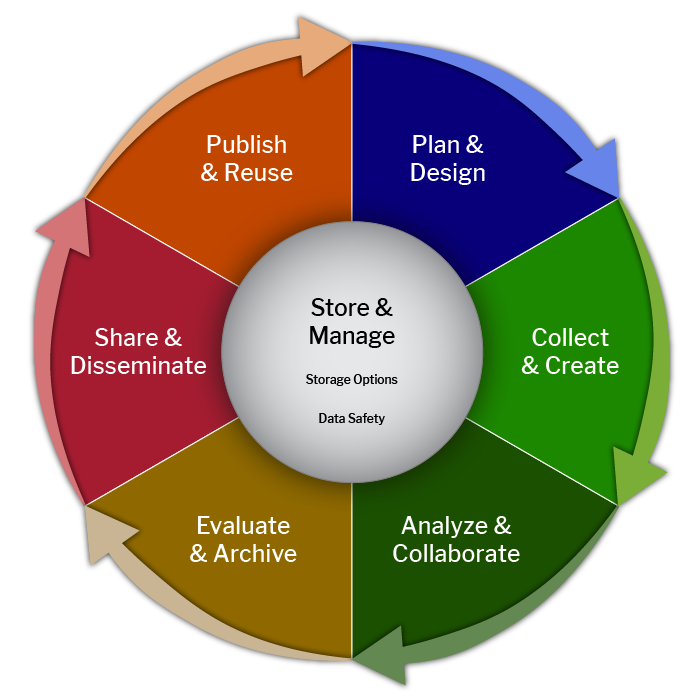

We often speak of the research data lifecycle when educating researchers about data management:

The research data lifecycle represents the stages of data collection, use, and reuse. How data is managed is integral to each step in the cycle. For example, when a researcher collects data, they should use standardized file naming and develop documentation to facilitate its interpretation and analysis. In order to analyze and collaborate, the researcher must organize their data and make it comprehensible to outside parties. In this lesson, we will focus on the data management plan, which should be composed during the “Plan & Design” stage, though it can be updated throughout the lifecycle.

The National Center for Data Services (part of the Network of the National Library for Medicine) defines Data Management Plans in their Data Glossary:

“A Data Management Plan (DMP or DMSP) details how data will be collected, processed, analyzed, described, preserved, and shared during the course of a research project. A data management plan that is associated with a research study must include comprehensive information about the data such as the types of data produced, the metadata standards used, the policies for access and sharing, and the plans for archiving and preserving data so that it is accessible over time. Data management plans ensure that data will be properly documented and available for use by other researchers in the future.*

Data management plans are often required by grant funding agencies, such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) or National Institute of Health (NIH), and are ~2-page documents submitted as part of a grant application process.”

A data management plan, sometimes also called a data management and sharing plan, is generally written by a researcher as part of the planning process before embarking on a project. Spending the time writing a DMP itself can clarify how to carry out data management tasks throughout the entire research data lifecycle. The process also creates a document that can be shared with lab staff or referenced as needed. DMPs are considered a living document and should be updated as circumstances inevitably change through the course of a research project.

Which of the following are uses of a DMP? (select all that apply)

- Component of a grant proposal to inform the agency of your data plans and funding needs.

- Planning how the project will manage its data.

- Creating documentation that can be referenced throughout the research process.

- Listing citations the researcher plans to use in their published paper.

- Component of a grant proposal to inform the agency of your data plans and funding needs.

- Planning how the project will manage its data.

- Creating documentation that can be referenced throughout the research process.

How often should a DMP be updated? (multiple choice, select one)

- Never. Data management plans are created during the funding proposal and need to be followed accurately.

- As needed. DMPs are living documents that are updated as circumstances change throughout the course of a research project.

- Constantly. DMPs should be written as you work on the project, and therefore should be updated every week during the data collection and analysis phases.

- As needed. DMPs are living documents that are updated as circumstances change throughout the course of a research project.

What are the components of a DMP?

The components of a DMP may vary depending on the funding agency. Always check the funding announcement for specific instructions on how your plan should be structured within your proposal and the level of detail required. In general, most DMPs will address the following five elements (each section is followed by an example):

Data Description and Format

The 2013 OSTP Memo defines data as “digital recorded factual material commonly accepted in the scientific community as necessary to validate research findings including data sets used to support scholarly publications, but does not include laboratory notebooks, preliminary analyses, drafts of scientific papers, plans for future research, peer review reports, communications with colleagues, or physical objects, such as laboratory specimens (OMB circular A-110)”. This section of a DMP provides a brief description of what data will be collected as part of the research project and their formats. Information about general files size (MB / GB per file) and estimated total number of files can be helpful. It is not necessary for researchers to describe their experimental process in this section.

Example

From a project examining the link between religion and sexual violence: This study will generate data primarily through (1) participant observations of support groups for those abused by clergy and (2) in-depth, semi-structured interviews with these individuals. Data will be collected via phone calls and video calls hosted on encrypted and passcode-protected conferencing platforms. Data will be collected in the form of audio recordings (MP3, collected on an external recording device free of any network connection), transcriptions of these recordings, physical notes taken during participant observation sessions, and any documents (e.g., email correspondences, scanned copies of letters or photographs) that respondents voluntarily choose to share with the researchers. All data in this study will be de-identified and associated with an anonymizing alpha-numeric code. The research team anticipates that most of these data will be preserved in DOCX, JPG, MP3, PDF, PNG, TXT, or XLSX format. Source (slightly modified)

Metadata and Data Standards

Metadata is information that describes, explains, locates, classifies, contextualizes, or documents an information resource (NNLM). Succinctly, metadata is data about data. A library catalog entry is an example of metadata. Metadata is compiled according to different standards: Dublin Core is an example of a general metadata schema. There are also specific metadata standards for different types of data: for example, MIAME and MINSEQE are commonly used for genomic data. We will discuss data standards further in Episode 2. This section provides information about what standards will be used, giving context to the data generated for easier interpretation and reuse. Often, discipline-specific data repositories will specify a particular metadata standard for their platform.

Example

From a project quantifying the ecological role of sea coral gardens at multiple spatial scales: Field observation data will be stored in flat ASCII files, which can be read easily by different software packages. Field data will include date, time, latitude, longitude, cast number, and depth, as appropriate. Metadata will be prepared in accordance with BCO-DMO conventions (i.e. using the BCO-DMO metadata forms) and will include detailed descriptions of collection and analysis procedures. Source

Preservation and Access Timeline

The data timeline includes information about when data will be backed-up, preserved, and published. Some agencies specify in their policies when the dataset must be shared, such as at the end of the reporting period (the active research phase). In addition to specifying their timelines, this section requires researchers consider what measures they need to take to ensure data security. Raw data may include identifiers such as PII or sensitive information such as location of endangered species that should be protected during collection and processing. Examples of good security practices include using access restrictions such as passwords, encryption, power supply backup, and virus and intruder protections. Active storage location and appropriate software will depend on data sensitivity level. In addition, before sharing any sensitive data with collaborators or depositing into a repository, the dataset should be de-identified or aggregated.

Callout

Although there are many data de-identification methods, it is beyond the scope of this lesson. For more information, please see the further reading resources on the reference page.

Example

From a project screening for protein biomarkers in human samples: Concomitant with publication of the results of the study, participant level data that have been stripped of demographic information will be published as supplementary data and/or made publicly available (with restricted access as laid out below) in the PI’s institutional data repository, which will mint a DOI and continue providing access for at least 10 years, or as long as the repository exists. Raw proteomics data and accompanying metadata will be made publicly available for at least 10 years. Source

Access and Reuse

Access refers to where the data will be made publicly available, and includes a justification why the repository chosen will help with dissemination, preservation, and reuse. In this section, researchers should also consider if their data will need to be embargoed, or if their dataset can only be published in a controlled access repository. Controlled access repositories require some form of verification before data can be accessed, and are commonly used for human subject research data. In addition, this section includes information on who can reuse the data, typically indicated by a license, and if reuse requires a data use (DUA) or data sharing agreement (DSA). In the event that data cannot be shared due to its sensitive nature, the researcher can use this section to specify why the dataset will not be published, including any ethical or legal issues around sharing data.

Example

For a project developing a diagnostic test to acne-causing bacteria: We will maintain a one-year embargo on data to organize and archive it, performing quality assurance checks prior to making in publicly available on one of the data sharing sites. Some species detected may be listed as endangered (Atlantic sturgeon, right whales) and these locations may not be publicly listed until management agencies have been notified and can protect the species involved. Intellectual property rights will reside with the persons identifying the species detected in passive acoustic data using data classification algorithms or by listening to the sounds. Identified species will have sample sound recordings deposited in the Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds (http://macaulaylibrary.org/). Geographic data of tracks of the AWG will be made publicly available as part of the ECU Coastal Atlas (http://www.ecu.edu/renci/Focus/NCCoastalAtlas.html). Acoustic tag Telemetry data detections will be archived in the Atlantic Telemetry Network (ACT http://www.theactnetwork.com/). Fluorometer data (Turner C3) are typically from a data stream taken at 1 to 2 Hz that is combined with CTD data as separate voltage channels into one file. Files will comprise a line of text for every second measurement, so if complexed with CTD data over long periods of time, they may reach GB size. We will submit our data to DataOne (https://www.dataone.org/). Source

Oversight

This section includes information on who is responsible for data oversight, which includes deciding how often or when actions such as backup, converting files to open access versions, depositing the data into a repository, long term preservation, and data destruction will occur. This also includes education for other members of the project team on the DMP and how to follow it. Generally, the PI is ultimately responsible for ensuring proper data management, but researchers may name any lab staff who will be working on data management as part of the oversight team.

Example

From a project examining the effects of placental dysfunction on brain growth in congenital heart disease: Lead PI and the eight co-investigators from the three sites mentioned above who are directly engaged in the research will be responsible for day-to-day oversight of data management activities and data sharing. Lead PI will meet monthly with key study personnel to ensure the timeliness of data entry and review data to ensure the quality of data entry. Lead PI will ensure that the metadata are sufficient and appropriate and that the data management and sharing plan follows the FAIR data principles. Lead PI will report the DMS related activities as outlined in this DMS plan in RPPR and request approval for a revised plan if there is any deviation from the approved DMS plan. At the project conclusion, the final progress report will summarize how the DMS objectives were fulfilled and provide links to the shared dataset(s). Source

Budget

Although most data management plans do not have a dedicated section on costs, data management should be considered when budgeting for a project, especially when writing a grant application. Costs associated with data management may include:

- Staff time for data management: writing documentation, curating data, maintaining data integrity

- Software to process and manage data

- Data storage above what is normally provided by the university

- De-identification services

- Repository deposit and curation fees

Quiz Questions: DMP Sections

Which information is not found within a DMP? (multiple choice, select one)

- File formats of the data

- Software, tools and code used to create this data

- What additional information (metadata) will be provided to allow for understanding the data, and what disciplinary standards it will follow

- The name of the journals where articles using this data will be published

- Schedules for backing up, publishing, and creating open format versions of files, including who is responsible

- Where the data will be published after the granting period and any conditions for reuse

- The name of the journals where articles using this data will be published

What information should be found within the data type section? (select all that apply)

- The general purpose of the project

- What data will be generated by the project

- What is the expected file type of the data

- How much data will be generated by the project

- How much data storage will cost

- Who in the research team will be responsible for collecting the data

- What data will be generated by the project

- What is the expected file type of the data

- How much data will be generated by the project

Match the sample text with the DMP component:

| 1. Data Description and format | a. We will use the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) for our data |

| 2. Metadata Standards | b. Data will be deposited in the Zenodo generalist data repository |

| 3. Preservation and Access Timeline | c. The PI will oversee implementation of this plan, with assistance from the lab data manager |

| 4. Access and Reuse | d. As required by the NIMH, we will upload our data in 6 months intervals from the beginning of the project. |

| 5. Oversight | e. We expect to collect 200 survey results, which will be stored in .csv format. |

1-e, 2-a, 3-d, 4-b, 5-c

Key Points

- Data management plans should be written during the planning phase of research and revised as needed.

- In general, a DMP should contain sections on data description and format, metadata and data standards, preservation and access timeline, access and reuse, oversight, and budget.

Content from DMP Resources

Last updated on 2024-05-10 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 28 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Where can one find Funder requirements?

- Example DMPs?

- Appropriate data repositories and data standards?

Objectives

- Find funder requirements for a DMP

- Successfully search for example DMPs

- Find FAIR data repositories appropriate for a patron’s research project

- Match a data type with appropriate data standards

Introduction

As librarians, we use a variety of resources to answer researchers’ questions, such as library databases like ERIC or PsycInfo, or reference sources like Credo. When answering data management plan questions, you will use a new set of resources. In this lesson, we will introduce you to places to find data management planning information to answer common researcher questions.

Funder Requirements

Funders are increasingly including DMPs in their requirements for grant applications. Due to the 2022 Ensuring Free, Immediate, and Equitable Access to Federally Funded Research memo, colloquially known as the “Nelson Memo”, all federal granting agencies in the US are required to establish data sharing policies. When assisting a researcher writing a DMP for a grant application, the first step is to get a handle on the funder’s requirements for the plan.

Here are some places to check for funder requirements:

The funding announcement. Most grant programs create an announcement, which may be called by any of a number of acronyms such as a “CFP” (call for proposals) or “NOFO” (Notice of funding opportunity) to publicize their funding opportunity. After navigating to the funding announcement, you can scan through the associated links to look for information on their data management plan requirements. Below, you can see the information provided in a National Institutes of Health Notice of Funding Opportunity:

In case the funding announcement does not have the information you need, proceed to the other items on this list.Funder application instructions or website. Large funders will have a website set up to help researchers through the application process. Looking through the documentation can help you understand their requirements for data management plans. This example from the NIH application instructions redirects you to sharing.nih.gov, their website specifically for data sharing:

The SPARC directory of data sharing requirements of federal agencies. SPARC stands for the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, and is a non-profit that supports open research and education systems. Through this website, you can view and compare data sharing policies from top funding organizations.

Google search. Often googling “[funder name]” “data sharing requirements” OR “data management plan” OR “dmp” will direct you to the appropriate documentation.

Contact the funder. If you are still not sure about what guidance to follow, consider reaching out to the research office contact in the funding announcement.

Example DMPs

After locating the funder requirements, researchers may find it useful to see an example DMP written by others as part of their application to the same program or funding agency.

Here are some places to check when looking for example DMPs:

University libguides. Many research university libraries have created libguides that provide researchers with guidance on writing DMPs. Some library resources include boilerplate templates for specific funding agencies, or successfully funded researcher DMPs. To find university libguides, you can either search through the LibGuides Community or search google for DMP AND [funding agency] AND libguide.

DMPTool. The DMPTool is a free online application that helps guide researchers through writing plans, and even allows librarians to provide feedback along the way. The website maintains templates based on funder and program requirements, in addition to hosting public DMPs created by researchers using the DMPTool. In the public DMPs list, you can narrow your search by funding agency to find relevant examples. We will explore the DMPTool more in Episode 4.

Funder example DMPs. Some funding agencies, like the NIH, have created example DMPs to provide researchers an idea of what they would like to see as part of their grant applications. In addition, some granting agencies share data management plans submitted as part of grant applications through a public repository. An example of this is the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) repository & open science access portal (rosap).

Example DMS plans website. The Working Group on NIH DMSP Guidance created the Example DMS Plans website, which aggregated stable versions of publicly available DMPs. It was compiled ahead of the rollout of the NIH DMS Policy.

FAIR Data Repositories

In data management, we often speak of making data “FAIR.” FAIR is an acronym for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. Using these principles, we can evaluate the “openness” of a data set. Repositories should promote these characteristics in order to make data housed there user-friendly.

According to the NNLM’s data glossary, “a repository is a tool to share, preserve, and discover research outputs, including but not limited to data or datasets.” Generally, a data repository is a website that houses a collection of datasets, making them available to a broad(er) audience. Repositories manage data sharing infrastructure and provide a stable location for researchers to share their work.

Why choose a data repository? For most researchers, a data repository is the best practice for data sharing. Using a personal or lab website or even uploading the dataset in journal article supplementary files is not advisable because the long term sustainability of the website is unknown: it can be updated or taken down without warning. In addition, simply adding “available upon request” to the data availability statement in a publication is not sufficient. Studies have demonstrated a lack of author compliance when data is actually requested.

Callout

In addition to lack of sustainability, personal websites, article supplementary files and availability upon request are typically difficult to find. Data repositories mints DOIs, digital object identifiers, providing persistent access to data even if it is updated or moved, and will provide reasoning for removal if the dataset needs to be taken down. Data repositories also provide structures that link README files or other metadata schemas to the dataset, allowing for greater reusability in the future.

Through repositories, several options are available to researchers for data sharing:

- Public access. Public datasets are available to all without restriction. This is commonly used for animal studies or data without privacy concerns.

- Controlled access. In a controlled access repository, researchers must verify their identity before they are allowed to download and analyze data. This can take the form of verifying a university-associated email address, signing a data use agreement, or sending in an application before access is granted. Some repositories, such as Vivli, which specializes in clinical trial data, require that sensitive data be analyzed in a controlled cloud computing environment. Others, like ICPSR, may require that their restricted datasets be accessed on-site, using a computer not connected to the internet.

- Embargoes. Most repositories allow for datasets to be embargoed. Data sets may be embargoed for a number of reasons. For example, the researchers may not wish to publish their data until the accompanying article is available, or they may be pursuing a patent based on their discoveries.

Here are the types of data repositories that researchers can use for sharing data:

- Specialist data repository. Specialist data repositories accept scholarships from certain disciplines or on a specific topic. These include ICPSR, the inter-university consortium for political and social research.

- Generalist data repository. Generalist data repositories accept any scholarship from any discipline. These include Figshare, Zenodo, Mendeley, and OSF. Other generalist repositories include Vivli, which only accepts clinical data, and Dryad, which primarily accepts data from the sciences.

- Institutional data repository. Some institutions host their own data repository to encourage their researchers to deposit data. These are typically limited to affiliates of the host institution, though you should check if your researcher’s collaborators are affiliated with an institution hosting a data repository. Other institutional repositories, like the Harvard Dataverse, allow any researcher to deposit their datasets regardless of affiliation.

Callout

Institutional repositories vary in their ability to accept and maintain data. Before commiting to using an institutional repository, check that they routinely accept data.

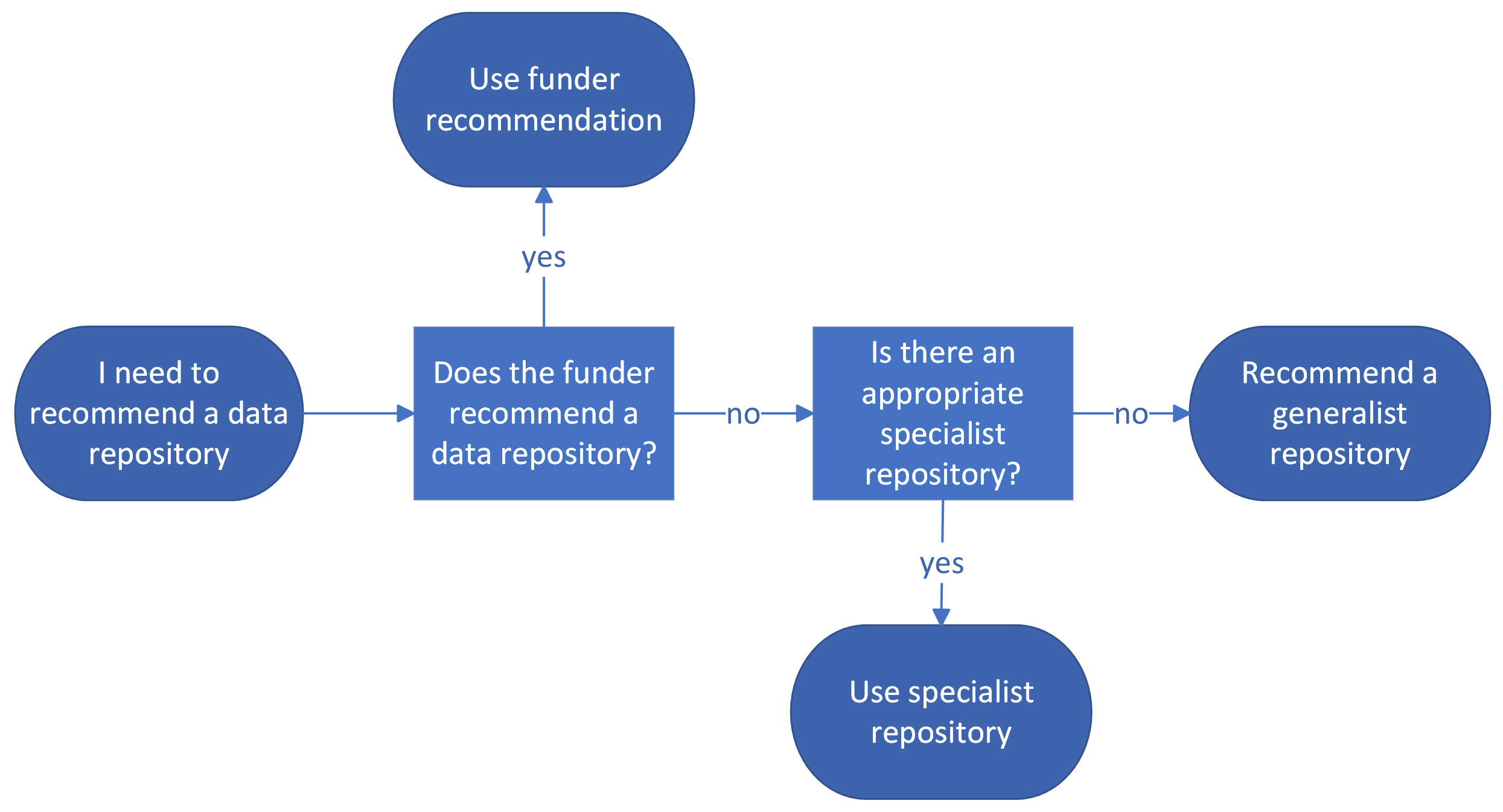

Recommending a data repository for inclusion in a DMP can be challenging. Generally, it is best to recommend a specialist repository, followed by an institutional or generalist repository. Here are some tools to help you find the right data repository for your researcher:

- Repository indices. Locating the right data repository for your researcher among the thousands in existence may be challenging, especially if you are not familiar with where others in the discipline are depositing their datasets. Luckily, there are a number of repository indices that aggregate data repositories and provide filters to facilitate pinpointing the one that works best for your researcher. FAIRsharing and re3data are good starting points when you are not aware if a specialist repository exists for a given discipline.

- Funder recommendations. Some funders like the AHA or the NIH provide recommendations for where their funded projects should share their data after the active research phase has concluded– the NNLM Data Repository Finder provides more guidance for finding an NIH-supported repository.

- Publisher recommendations. For researchers without funding or whose funders provided no guidance on which data repositories to use, some publishers like Nature have requirements where researchers should deposit their data before their articles are published.

Callout

Publishers requiring data deposit before article publication will also require a data availability statement, a description of where the dataset is publicly available, located at the bottom of the article.

Metadata and data standards

According to the NNLM data glossary, a data standard is “a type of standard, which is an agreed upon approach to allow for consistent measurement, qualification or exchange of an object, process, or unit of information. […] Data standards refer to methods of organizing, documenting, and formatting data in order to aid in data aggregation, sharing and reuse.”

Data standards help to promote the FAIR principles. By using a data standard when creating and describing their data, researchers make their data easier to discover and reuse. For instance, if you use a standardized survey instrument when collecting data, your data can be easily compared and combined with the results of other researchers using the same instrument.

Some of the most common data management questions data librarians receive revolve around standards. Many researchers, even if they support the principles of open science, are not trained to find and utilize data standards. Often, they are not thinking about their process from the point of view of data reuse. For librarians, data standards present an opportunity for us to educate researchers.

There are many types of data standards, including:

- File type. When curating a dataset to share, researchers should convert their data to an open file format. For instance, spreadsheets should be made available as a CSV rather than an excel document (XLSX). Using standardized open file types is a data standard.

- Controlled vocabularies/ontologies. A controlled vocabulary ensures data standardization by limiting the number of terms that can be used in a given field. Librarians often use controlled vocabularies when cataloging, for example MESH for medical subject terms, or the Getty AAT for art terms. Researchers can also use controlled vocabularies in their work to ensure interoperability across studies.

- Minimum information. Minimum information standards, such as the MINSEQE, specify the minimum amount of metadata and data required for different data types. This helps to facilitate reuse and prevent mystery datasets without documentation from coming into a repository.

- Metadata schema. A metadata schema defines the elements of metadata for an object and how those elements can be used to describe a specific resource. Many librarians are familiar with metadata schemas such as MARC or Dublin Core, but there are also specialized metadata schemas for particular research fields.

Finding appropriate data standards can be tricky for both librarians and researchers. The data standard landscape is still evolving, and the availability of data standards varies widely by field. There may be no widely accepted standard for a researcher’s project. If there is a lack of appropriate data standards, this information should be included in the DMP.

One strategy when answering reference questions about data standards is to work backwards. If you or the researcher have already picked out a data repository, look in the documentation of that repository to find what data standards they are using. For example, the NIMH National Data Archive has a page describing their data standards.

If working backwards isn’t possible, here are some resources to find data standards:

- Research data alliance metadata standards catalog

- Fairsharing has a registry of standards

- Bioportal Ontologies catalogs ontologies, with a biomedical focus

- DCC guide to disciplinary metadata standards catalogs standards, tools, and use cases by subject area

Quiz

As part of an intervention study, a researcher will be conducting surveys of adolescents in the juvenile justice system who have exhibited suicidal behavior. In addition to surveys, there will be in-depth interviews with some of the research subjects. The results will eventually be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Accordingly, the datasets will be shared and preserved. The researcher has learned that their University has an institutional repository that has not typically collected scientific data.

Which of the data types mentioned would be applicable to the data management plan?

- The interviews (qualitative)

- The survey data (quantitative)

- Both

- Both

What aspects of managing and sharing this data should this researcher consider as they prepare their data management plan?

- The choice of repository.

- Usage of standard questionnaires for the survey.

- Facilitating the potential reuse of the data.

- All of the above

- All of the above

ICPSR

The example study contains sensitive data because it deals with a non-adult incarcerated sample exhibiting suicidal behavior. In order to be shared, it requires additional safeguards. Dryad does not have a controlled access feature and therefore is not an appropriate choice in this case. ICPSR aligns more with the discipline of this study, and requires researcher screening and secure access before data can be viewed.

- Answers will vary, but one acceptable response is Vivli. To find which data repositories accept clinical trial data, use the NNLM data repository finder and check off “Clinical Trials” under question 4.

- Answers will vary. We can see Vivli’s guidance on data standards%20used%20for%20analysis.), where they recommend following CDISC standards.

Key Points

- Librarians need to be able to find funder requirements, example DMPs, data repositories and data standards to answer researcher questions.

Content from Supporting Researchers

Last updated on 2024-01-16 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 32 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How does a data interview compare to a reference interview?

- What are common researcher questions about the DMP process?

Objectives

- Identify the difference between a data interview and a reference interview

- Construct questions for a data interview

- Answer common researcher questions about the DMP process

Introduction

So far, we have covered what a data management plan looks like, what each subsection contains, and where to locate resources that connect to the researcher’s specific need. In this section, we pivot from learning about DMPs into how to apply this knowledge when serving patrons. We will provide insights into common questions and concerns researchers have about the DMP process, and describe strategies on how to effectively conduct a data interview.

Data Interview

According to the NNLM’s data glossary, “a data interview in the library context refers to an interaction between a librarian and a researcher with a structured or semi-structured set of questions designed to elicit information about the researcher’s data practices and/or needs.” This process is essentially a specialized subcategory of the reference interview, and is a good first step in helping a researcher prepare a DMP.

Just like the reference interview begins with establishing a background purpose (“what is this information being used for”), you might want to begin broadly by asking researchers about their project and its purpose. This can help you to begin formulating follow-up questions that will extrapolate the researcher’s needs.

Challenge

Let’s say that the researcher responds with “I am running a project about the impact of pets on the emotional well-being of children” to the question “what is the purpose of your research”.

What has this short response told you about the researcher’s project and needs?

Children are the subject of the research, so it is a human subject’s study. This means that researcher will probably need additional accommodations if they want to share their dataset. Children are also a protected population, which needs to be taken account when trying to answer the question should data be shared. Based on the information provided it is unclear what format the data will be in (Observational notes? Quantitative questionnaire responses? Qualitative interviews? Other?), and will therefore need to be explored more during the conversation.

Even short responses can give you an idea of who/what is the subject of the research, how sensitive this data may be, and the potential formats of the data. Even with this short response, you have already found out this is a human subjects study, and that this researcher will need additional accommodations if they want to share their dataset. Like in a reference interview, it is useful to paraphrase the project back to the researcher and ask clarifying questions to make sure you have a good grasp of the research purpose.

After establishing the purpose of the project, it is helpful to ask about where the researcher is applying for grant funding and their timeline for submitting materials. Researchers who are not applying for grant funding can still benefit from writing a data management plan, and these questions can help them consider their project needs and what workflows need to be put into place.

Next, we move on to follow-up questions that relate to the DMP sections. Like in a reference interview, these questions move from open-ended to closed, specific questions to clarify needs not raised by the researcher. Use the purpose of the project to inform your questions, and help the researcher think through their workflow and needs. Sometimes the researcher will answer “I am not sure”. This is an opportunity to explore what they think they will do, and to provide some options as to how they may proceed. Remind the researcher that a DMP can (and should) be updated as necessary to better align with their procedures as the project evolves.

Instructors might take this opportunity to use the sample researcher response or some other project to help learners brainstorm questions within each section. Answers to these challenges can be found in episode 1.

Follow-up questions on data description and size

Let’s start with the first DMP section “Data Description and Format”.

Challenge

What information should this section contain?

This section of a DMP provides a brief description of what data will be collected as part of the research project and their formats. Information about general files size (MB / GB per file) and estimated total number of files can be helpful.

To summarize, we are looking for WHAT data will be generated and HOW MUCH data will be generated, both in terms of size and quantity.

What sort of questions can we ask to get at this information?

- What is your target sample size?

- How are you collecting data?

- Are you using structured questionnaires or interviews?

- Are you interacting with subjects directly or indirectly?

- Talking with the subject

- Talking to their guardians or a third party

- Recording observation

- Are you taking video, audio recordings, or images?

- What devices are you using?

- For videos/audio recordings, how long are the recordings? In what format?

- Are you collecting data any other way?

- Scans

- Measurements

- Is the collected data in a physical format (such as on paper) or in a digital format (through a computer or other electronic device)?

- How often are you collecting information for each subject throughout the study?

Follow-up questions on metadata and data standards

Challenge

What information should this section contain?

This section provides information about what standards will be used, giving context to the data generated for easier interpretation and reuse.

To summarize, we are looking for HOW data is documented, and how that documentation is standardized to make it easier to understand and reuse.

What sort of questions can we ask to get at this information?

- How are you documenting your variables?

- Are you using abbreviations that need defining?

- Does your data have units that need clarification?

- Are you using derived variables (variables obtained by combining or coding other variables)?

- Does your discipline have any requirements for how you should be

describing your dataset?

- Are you using a set of words standard to your field (controlled vocabulary)?

- What minimum information would colleagues need to know to

- Recreate your research study?

- Recreate your analyses?

Follow-up questions on preservation and access

Challenge

What information should this section contain?

This section provides information about when data will be backed-up, preserved, and published, as well as data security.

To summarize, we are looking for HOW data is secured as well as preserved for future access.

What sort of questions can we ask to get at this information?

- Where are you storing the paper copies of the questionnaires?

- Where are you storing the audio recordings of your interviews?

- Are you planning on transcribing your interviews?

- What software are you using to

- code your data (Excel, Google sheets, SPSS etc)?

- analyze your data?

- Have you considered file naming conventions or file structures to help you find your files more easily?

- If using a proprietary software, are you planning on saving your files in an open format for sharing and long-term preservation?

Callout

Proprietary software is owned by an organization that requires a license or a fee to access. Typically, this software will generate files formats specific to it (such as Excel .xlsx), and it might be difficult to open or manipulate it using other software. Converting these data files into an open format, a version that is easily accessible by many pieces of software, makes data more FAIR (such as from .xlsx to .csv or .tsv). For a list of open access file formats, please see the resources on the references page.

Follow-up questions on access and reuse

Challenge

What information should this section contain?

This section provides information about where the data will be made publicly available, and includes a justification why the repository chosen will help with dissemination, preservation, and reuse.

To summarize, we are looking for WHERE data is stored long-term, and why it is the best choice for discovery, reuse and preservation.

What sort of questions can we ask to get at this information?

- Are you planning on sharing your data in the future?

- Do you have any obligations from your funder to share your data?

- Where are you planning on publishing your articles? Does the publisher have any data sharing requirements?

- If you are planning on sharing your data in the future, is data sharing explicitly addressed in the consent form?

- If you are planning on sharing data in the future, do you have a

sense of where you want to deposit your research data when the time

comes?

- Discuss repository options

- Do you need to de-identify or aggregate your data before you can

share your data?

- Discuss embargoes, controlled vs open access

Follow-up questions on oversight

Challenge

What information should this section contain?

This section provides information about who is responsible for data oversight, which includes deciding how often or when actions such as backup, converting files to open access versions, depositing the data into a repository, long term preservation, and data destruction will occur.

To summarize, we are looking for WHO takes responsibility for the data during the project, in the short and long term, and ON WHAT timeline.

What sort of questions can we ask to get at this information?

- Who is coding your data? How are you maintaining accuracy?

- Data checks? Double entry? Controlled entry?

- Who is responsible for backing up your data? How often?

- Who is responsible for preserving your data long term?

- Who is responsible for depositing your data?

Callout

Researchers may ask if they can list you as the librarian for helping them plan the data management activities specified in the DMP. Unless they are compensating you for your time and writing your name into the grant to manage the data on the project, remind them that this section is for listing who is carrying out these activities. Typically, the PI (primary investigator) is responsible for this activity, however lab managers or other staff may also be listed.

Follow-up questions on budget

Consider costs associated with data management.

- Where are you planning on storing your data during the active research phase?

- Do you need additional or specific types of platforms that the university does not provide? Do these have costs?

- Do you need to pay someone to manage your research data?

- Do you need to pay for data de-identification or curation?

- Do you need to pay for your dataset deposit?

Tips for talking with researchers

- Researchers may have not been formally trained in data management and may not think about their project through this lens

- Researchers often speak a different language - they may assign a different meaning to metadata or data standards

- Researchers may not be accustomed to submitting data to a repository

- There are many reasons a researcher may be hesitant to share their data. This can include a lack of sharing culture within their disciple, fear of their research getting “scooped” (having your research idea or results published by someone else), or the additional labor associated with preparing their dataset after the active research phase.

Mock Data Interview

Conduct a data interview with a classmate. The “researcher” will read the scenario below, but the “librarian” will not. The researcher can feel free to fill in any details needed to answer the questions from the librarian – these scenarios have been left intentionally domain agnostic. Then switch.

Scenario 1: You are a researcher writing a grant

proposal to be submitted to the NIH. You have heard that a data

management and sharing plan is required for NIH grant applications, but

you don’t know any details.

Scenario 2: You are a researcher working to publish an

article in a journal. You have just found out you need to make your data

open by depositing it in a repository to satisfy journal requirements.

You aren’t sure which repository to choose.

Key Points

- A data interview is related to, but not the same as the reference interview.

- Use the follow up questions in this section in your data interview to elicit the information needed to improve researcher DMPs.

- Researchers may be new to sharing data and data management

Content from DMPTool and Common DMP Issues

Last updated on 2024-03-22 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 31 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How does DMPTool help librarians and researchers?

- What are the capabilities of the DMPTool at different access levels?

- What are some common DMP issues?

- What should a librarian look for in providing feedback on a DMP draft?

Objectives

- Navigate the DMPTool website

- Provide constructive feedback on a DMP draft

Introduction

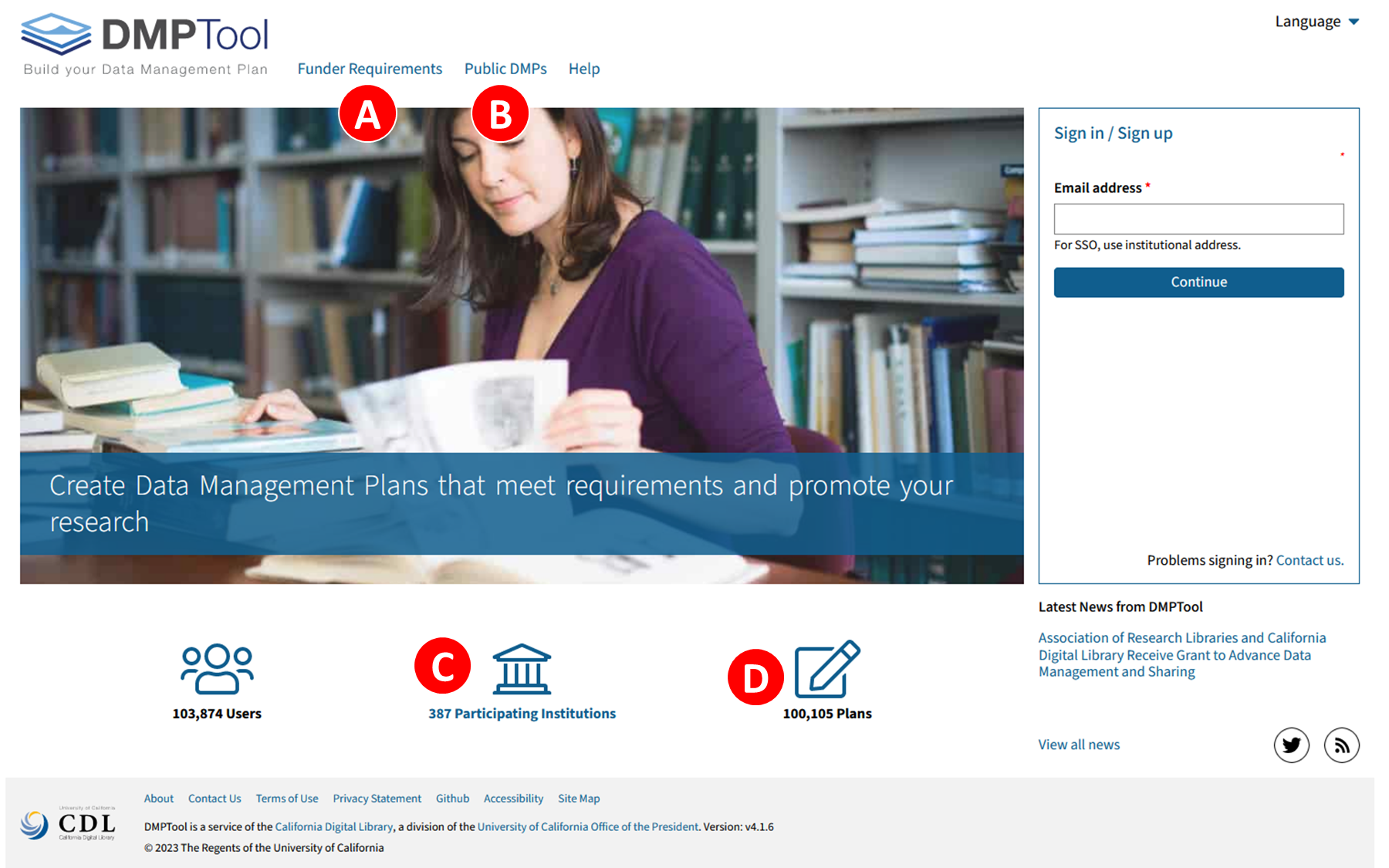

DMPTool is a free, open-source, online application that helps researchers create data management plans. The tool provides a click-through wizard for creating a DMP that complies with funder requirements. DMPTool is a service run by the California Digital Library.

The DMPTool is meant to be a one-stop shop that benefits both the researcher and librarian or other support staff. The website includes links to funder requirements and sample plans. Researchers can create plans in a wizard that includes side-by-side instruction. Participating institutions have the option of preparing templates with customized guidance for their institution and utilizing the feedback system to review plans by request.

Capabilities of DMPTool by access level

When teaching this lesson, we suggest doing the following demo live. You can watch the video to get an idea of features to cover.

Some features of DMPTool are accessible without logging in. Watch this short video to see how to:

- Look up funder requirements

- Search for sample DMPs

- See a list of participating institutions

Activity

Go to the DMPTool and click on “participating institutions” to find out if your institution is on the list. If so, you may log in to the platform using your institutional account or Single Sign On (SSO). If you are an administrator (librarian or otherwise) and want to learn more about becoming a participating institution, please contact the DMPTool administrators.

One can log into the DMPTool using their SSO or by setting up an individual account. Watch this video for a demonstration by a user from a participating institution on how to:

Find DMP plans shared by other researchers at your institution

Create a plan

-

Request feedback

The highest level of access available is granted to the site administrator at your institution who may be someone in the library or in a different research support unit. The capabilities available at the admin level include:

- Prepare DMP templates or custom guidelines for established templates

- Respond to feedback request from researchers

- View plans created at your institution and a list of registered users

Callout

For more resources on using the DMPTool as an administrator, please see the references page.

Knowledge Check

Q1. Example data management plans are available without logging in to

the DMPTool. Which option should I click on to find example data

management plans?

- “Funder Requirements”

- “Public DMPs”

- “Participating institutions”

- “100,105 plans”

Choice B is correct. There are over 100 public plans available. Choice D is not a link - it’s a tally number of DMP made using this tool.

Knowledge Check (continued)

Q2. For participating institutions, it is possible to find plans

developed by researchers at your institution. After logging in to

DMPTool, where would you click to find these plans:

- “My Dashboard”

- “Create Plan”

- “University name”

- “Admin”

Choice A is correct. At the bottom of your dashboard you can see plans for your instition. This section shows plans from all authors who gave permission to share their plan.

Common DMP Issues

Below are some common issues, how they can be identified, and constructive feedback that can be provided to improve the DMP. As you begin to assist researchers with data management planning and revising their DMPs, you too will notice these and other trends that will make issues easier to spot in the future.

Callout

Please note that constructive feedback may differ if the research agrees to a consultation, or if you are providing feedback through email or the DMPTool.

Language was copied from another project or template without modifications

How can you tell?

- The DMP reads like several different projects

- The verbally stated goals of the project are not aligned with what is written in the DMP

- The action items in the DMP are not appropriate for the project

Why this is an issue:

- By copying and pasting existing language, researchers may not understand what they are promising the granting agency

- Researchers also miss out on examining their own processes and creating a plan that fits with their workflow

Constructive feedback:

- In a consultation, ask the researcher if they used language from another template or plan, and if they understood everything they were proposing. Go through each section and use the data interview questions in Episode 3 to help the researcher customize the plan to their needs.

- In the DMPTool or email, call out the sections that do not make sense for the project. Suggest that they consider how to modify the template language to better fit with their project workflow and make it easier to follow-through to meet funder requirements. Offer to schedule a consultation to discuss this more in person.

Including additional information that does not qualify as research data

How can you tell?

- Listed information includes “laboratory notebooks, preliminary analyses, drafts of scientific papers, plans for future research, peer review reports, communications with colleagues, or physical objects, such as laboratory specimens”, which do not fall under the research data definition (OMB circular A-110)

- Includes other information that does not fall under this definition include evaluating student performance or courses as part of the project (data reported to the institution)

- Lists other scholarship generated as part of this research project, such as which journals will be targeted for articles publications and which conferences will be attended to present findings

Why this is an issue:

- Non-research data has no place in a DMP. It does not need to be publicly accessible or preserved as part of funding requirements

Constructive feedback:

- Provide researchers with the research data definition, identify which information does not fall within the definition, and suggest that they remove it from their plan

The Data Description and Format section does not contain sufficient data information

How can you tell?

- There is no information about what data will be collected or what tools will be used to collect this information

- There is no information about file formats and types

- There are no files size estimates

Why this is an issue:

- It is difficult to plan for data management if the data to be generated within a project is not specified

- It is possible that researchers do not have a good understanding of what counts as research data, which will make follow through on the plan difficult

- It is also possible that researchers do not want to provide estimates or assumptions, but lack of information prevents the funding agency from understanding their project fully

Constructive feedback:

- Using the information in Episode 1, state what information you were hoping to see in this section. It may also be helpful to provide sample language to give researchers a sense of what level of detail is expected in this section

- Offer to schedule a consultation to help the researcher brainstorm what data might be generated as part of their project. Remind them that their best estimates should be included for now, and that the DMP can be updated once they have solidified their workflow

The Metadata and Data Standards section does not contain sufficient data information

How can you tell?

- The section has been completely omitted

- There is no information included about disciplinary standards

- There is no information included about metadata

- Information in this section is incorrect

Why this is an issue:

- Sharing a dataset without metadata to explain variables and provide context renders it useless to those trying to reuse it

Constructive feedback:

- Using the information in Episode 2, suggest standards to the researcher. You might also provide sample language from Episode 1 to give researchers a better idea of how others have filled out this section

- Ask researchers to consider what the minimum information they need to provide so that colleagues can understand their variables and replicate their analyses

- Ask researchers if there are any controlled vocabularies within their discipline that they will be using as part of the project

The Access and Reuse section does not contain sufficient data information

How can you tell?

- The researcher states that data will not be shared and provides no further information

- The researcher does not provide any information about data sharing, only that it will be destroyed (or maintained privately)

- The researcher states that data will be shared only after a specific event later than the time specified by the funder guidelines (e.g., researcher retirement, researcher death)

- The researcher is overly restrictive in sharing nonsensitive data (eg., animal studies)

Why this is an issue:

- Federally-funded research uses tax-payer money, and thus, should be made accessible to the public as widely and as soon as possible. Limiting the sharing of research results also limits research advancement through collaboration and limits the public’s access to information. Sometimes data sharing is not possible because of the sensitive nature of the dataset. However, reasons for not sharing the dataset in a limited capacity (in aggregate, by using extra precautions such as data use agreements or controlled access repositories) needs to be clearly stated. Omitting this information prevents the funding agency from understanding their project accurately

- Not sharing because of the additional labor involved or the lack of data sharing within the discipline are not adequate reasons

Constructive feedback:

- Introduce the researcher to the concept of a data repository, explaining that it provides long-term sustainable access to datasets for free

- Ask researchers if there are any specific reasons why they cannot share their data. Encourage them to state these reasons clearly if the data is sensitive. Otherwise, using the information in Episode 2, make repository recommendations (prioritizing a specialist repository over an institutional or generalist repository)

The location of dataset sharing provided in the Access and Reuse section is unsustainable

How can you tell?

- The researcher states that they will make the data available in the supplementary files as part of the article publication

- The researcher states that they will make the data available on their personal or university website

- The researcher states that they will build their own repository for storing the data

- The researcher states that they will make the data available by request

Why this is an issue:

- As stated in Episode 2, making the dataset available as a supplementary file or on a personal website is not advisable because the long term sustainability of the website is unknown: it can be updated or taken down without warning

- Making the data available only by request is also not sustainable because it requires the researcher to find, evaluate and curate the data every time it is requested. Moreover, email addresses change when researchers move institutions or retire. Studies have demonstrated a lack of author compliance when data is actually requested.

- Building their own repository for storing data is unsustainable because it requires time, resources, and maintenance. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when there are data repositories maintained by well-funded entities that are free to use.

Constructive feedback:

- Introduce the researcher to the concept of a data repository, explaining that it provides long-term sustainable access to datasets for free

- Ask researchers if they are aware of any funder or publisher data repository recommendations that they can follow. Otherwise, make repository recommendations using the information in Episode 2.

Quiz Questions: Find The Issue

Choose the right issue with the following passages from example DMPs.

- “The amount of data generated by this research will be quite small (less than 2 GB), and we believe that it will not be of interest to other researchers. However, we will provide our raw data via email to any researchers who contact us.”

- Overly restrictive in data sharing

- No data standards mentioned

- No size estimation

Choice A

Quiz Questions: Find The Issue (continued)

- “As part of this project, we intend to present a poster yearly at our society conference meeting. We intend to publish a research protocol in [name of journal] and our final paper in [name of journal].”

- Noncompliance with funder data sharing requirements

- Information not required in a DMP

- Lack of stated data file formats

Choice B

Key Points

- The DMPTool is a click through wizard that helps researchers create a compliant DMP.

- If they are in a member institution, librarians can provide guidance and give feedback to researchers through the DMPTool.

- Librarians will see similar issues in researcher DMPs over and over. Use the guidance in this section to prepare.

Content from Data Management Plan Services

Last updated on 2024-04-01 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What data management plan services are usually offered by research institutions?

- What stakeholders should be involved in planning data management plan services?

- What professional groups can provide training on creating and running DMP services?

Objectives

- List options for data management plan services/programs

- Brainstorm stakeholders to contact

- Predict potential challenges in implementing data services at your institution

Introduction

Now that you have learned about DMPs and how to address common issues, you are prepared to think about how to implement support at your institution. This lesson covers options for data management planning services and how to implement a new data program. It is important to keep in mind that the information in this module was drawn from the authors’ own experiences as data librarians and not all of the options may be applicable for your institution.

Stakeholders

When embarking on a new data service in the library, often the first step is to contact stakeholders at your institution. These are individuals who support related services in their own departments, and can give you ideas for what gaps exist at your institution, and how you can most effectively implement or publicize your new program. Some stakeholders will be people you likely already know from your library work, and some may be new to you. Please note offices and groups may go by different names at your institution than the examples provided below.

- Research and funding. This includes the Office of Research, Office of Undergraduate/Graduate Research, Research Institute, Research Administration, Grants Management, and Office of Sponsored Programs (or your local equivalent). These offices usually have contact with a variety of researchers at your institution and will have information on their needs. They may also be partners for presentations or publicity.

- Compliance. This includes Institutional Review Board (IRB), Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), the Research Integrity Officer (RIO), and Regulatory Affairs (or local equivalents). These offices usually work on ensuring that researchers are following funder mandates on data sharing.

- Research IT. This includes Research Computing, High-Performance Computing, and Information Security (or local equivalents). Your research IT can inform about options for data storage and sharing on campus. It’s also helpful to have a contact person there to refer questions to.

- Data and Statistical Analysis. This includes Statistical Consulting, Biostatistics, and Institutional Statisticians (or local equivalents). These people are useful contacts for referring out questions on statistical analysis. They may also be able to point out common issues that researchers are facing that can be addressed via library instruction.

- Research Support Services. This includes the Office of Teaching and Learning, Research Coordinators, Research Training, and liaison librarians (or local equivalent). These units already teach and support researchers, and may have insights into knowledge gaps. You can also cross-promote any events.

- Anyone involved in intellectual property or data licensing. The offices involved in this area vary widely by institution, but can include the General Counsel or the Office of Intellectual Property. These people are helpful to refer out questions on data licensing, patents, or institutional data use agreements (DUAs).

Professional Organizations

Like all varieties of librarian, data librarians have their own organizations and networking groups. Joining some of these groups can be a great way to get support as someone new to the field. Here are some options to get you started:

- Data Curation Network – Data curation network provides resources and professional education opportunities for anyone working in data curation, data management, or data repositories.

- NNLM National Center for Data Services – Provides education, training and resources for data librarians in the health sciences.

- Research Data Access and Preservation Association (RDAP) – Professional association for those creating, maintaining, advancing and teaching best practices for research data, access and preservation. RDAP has a very useful listserv.

- Research Data Alliance - Organization of member institutions devoted to enabling open sharing and reuse of data. Provides training and events.

Data Management Plan Services

Data Management Plan Consultations

In libraries that provide DMP services, the most common offerings are data management plan consultations. We discussed how to provide a data consultation in Episode 3. Research data consultations can be an easy way to integrate DMP support into your offerings, as these questions can be asked during regular research consultations or email communications to determine research needs. Keep in mind that it is important to build up your network of internal data stakeholders before taking on data reference, since it is common for questions to be referred out to other units at your institution.

DMP Draft Review

Many libraries also review drafts of data management plans after they are written. This includes cross-checking the DMPs with any funding agency requirements, and review of completeness and feasibility. DMP review can also be done through the DMPTool, as detailed in Episode 4. When establishing a DMP draft review service, it is important to consider how you will balance completing the reviews with your current workload. Many researchers write DMPs for grants at the last minute, and so some libraries have implemented rules to limit requests with a tight turnaround time. For example, you may want to enact a policy requiring DMP review requests to be submitted a week or more before the grant deadline.

Educational Programming

In addition to providing one-on-one services for individual researchers, you may want to incorporate larger educational programs on DMPs. Librarians can incorporate asynchronous education by creating libguides linking to DMP resources, or providing instructions on how to write DMPs for specific granting agencies (e.g. the NIH, NSF). Using the LibGuides Community mentioned in Episode 2, you can find and remix a DMP libguide that serves your community’s needs best. Libraries can also target audiences synchronously by providing webinars or education sessions on writing a DMP, DMP policies or requirements, and using the DMPTool.

Marketing

As with any other new library program, you will need to market your DMP services. For example, you might use flyers, email lists, digital signage, or postcards through the campus mail. Successful marketing strategies vary from institution to institution, and you know your institution best. However, taking advantage of your stakeholder network to reach out to data-intensive researchers is important for successfully marketing a data program.

Key Points

- When preparing to start DMP services in your library, reach out to other institutional stakeholders for collaboration.

- Join a professional organization to get support from other librarians.

- There are many possible data services libraries can provide. Pick whichever one suits your institution best.