Introduction to Qualitative Data

Last updated on 2024-06-21 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What can we learn from existing qualitative data?

- How is qualitative interview data typically structured?

Objectives

- Appreciate the goals and approach of this lesson

- Identify opportunities and barriers for qualitative data reuse

- Practice finding and downloading data from a qualitative data repository

For decades, a movement has been building among quantitative researchers to share data and analysis as completely as possible. In part, this is meant to improve scientific transparency, so findings can be checked and verified, but it also serves to provide a basis for future studies.

Qualitative researchers have been much slower to adopt data and analysis sharing, for a few different reasons, including both technical and normative constraints. On the technical side, qualitative data has had limited standards, and analysis has often been conducted manually or with specialized software with limited compatibility with other software. More importantly, however, qualitative researchers tend to emphasize the role of both the context of data collection and the perspective of the researcher in the research process - in contrast to quantitative methods that often seek precisely to minimize the subjectivity of their methods and draw wide-ranging conclusions about entire populations.

Moreover, qualitative data often presents challenges for protecting privacy when sharing data, because interviews, focus groups, and other qualitative methods provide rich detail that can make it easier to identify participants even if direct identifiers are removed, as well as often dealing with sensitive issues.

Despite these challenges, however, there is a small but growing movement to share and reuse qualitative and mixed methods data and analysis, helped along by recent technical developments.

In this lesson, we will start by exploring what advantages sharing and reusing qualitative research can offer that might offset the challenges it presents, then practice finding, reusing, and sharing data and analysis projects with the largest qualitative data archive, QDR, and the most widely used coding and qualitative data analysis software, NVivo.

The data we will work with are real data, although the scenario we use is somewhat artificial. Our goal is twofold - to help build literacy and skills for working with secondary qualitative data using relevant tools and to help develop an imagination for how you might reuse and share qualitative and mixed methods data to improve your own research.

Reusing Qualitative Data

The first step to reuse is to understand what elements might be reused and why. Historically, research products like articles and books have been the primary shared output of qualitative research. However, there are at least four other common research products that may be valuable for reuse or adaptation:

- methodologies and instruments

- raw data

- codebooks

- analysis

In the next step, we’ll download some real qualitative data and explore how each of these products might be useful to another researcher.

Types of data

Throughout this lesson, we’ll be using semi-structured interviews, one of the most common types of qualitative data, in our examples and discussion. Content analysis generally involves similar concerns and processes, but uses other kinds of secondary data, such as published print or audio-visual materials. Other qualitative methods, such as participant observation and focus groups, may be somewhat less suited to these tools and approaches and may require adaptation beyond what is discussed here.

Part of the power of qualitative research is its recognition that no method can be truly universal and that all analysis is contextual. We encourage you to treat the discussion and tools here as starting points, rather than templates.

Finding and Downloading QDR Data

Discussing data reuse in the abstract can only get you so far. Instead, we will imagine we face the following scenario and working together to discover how we can take advantage of others hard work to improve our research:

You are preparing to conduct a study of social media users in multiple countries, with a focus on understanding how people make decisions about the privacy of their posts and profiles.

Participants will complete brief surveys about their demographic background, participate in one or more semi-structured interviews, and provide access to their posts on each platform they regularly use for a period of 1 month. You are the lead researcher, but are joined by both long-term collaborators and student research assistants, who are likely to come and go throughout the expected duration of the research.

Your training in qualitative research makes you skeptical of the value of data that was collected for other purposes, but you also know you won’t have much time to collect the data and need to ensure you make the most of the opportunity and structure your interviews so they can reveal critical findings.

One of your collaborators referenced a dissertation that used qualitative methods to study data sharing in qualitative and big social research, and you noticed that the dissertation mentioned that anonymized data are available online. Although your research questions differ from theirs, you wonder if their interviews might help guide how you approach your study and decide to take a look.

The first step to finding out whether this data can help is to get the data.

Following the link in the dissertation, visit the data’s summary page at the Qualitative Data Repository, or QDR. QDR describes itself as

…a dedicated archive for storing and sharing digital data (and accompanying documentation) generated or collected through qualitative and multi-method research in the social sciences and related disciplines.

Essentially, QDR is a place for researchers to share qualitative and mixed methods data in a variety of forms, as well as their analysis projects. Some data are restricted and require an application or agreement before using, but other data, including what we are interested in, are openly available to any registered user.

Before going to the trouble of registering, let’s take a look at what is actually available in this data collection.

The description, once expanded with the

Read full description button summarizes the project,

research questions, data collection process, and what is included in the

collection here.

Assessing usefulness

Spend a few minutes reading the description and discuss with a partner how helpful you think this data might be for the social media privacy project and why.

This project contains a wide variety of information, including:

- interview transcripts from three different populations

- interview analysis

- participant summaries

- interview guides

- study documents (consent forms, solicitations, IRB)

Both the topic and the range of data available seem promising, and the QDR Standard Access license agreement allows any registered user to download the data, so let’s download it and see what we find!

If you don’t already have one, you’ll need to create an account at

QDR for the next step. To do so, click Register. in the top right

of the summary page. Fill out the registration form and click

Create new account, performing any necessary verification

before proceeding.

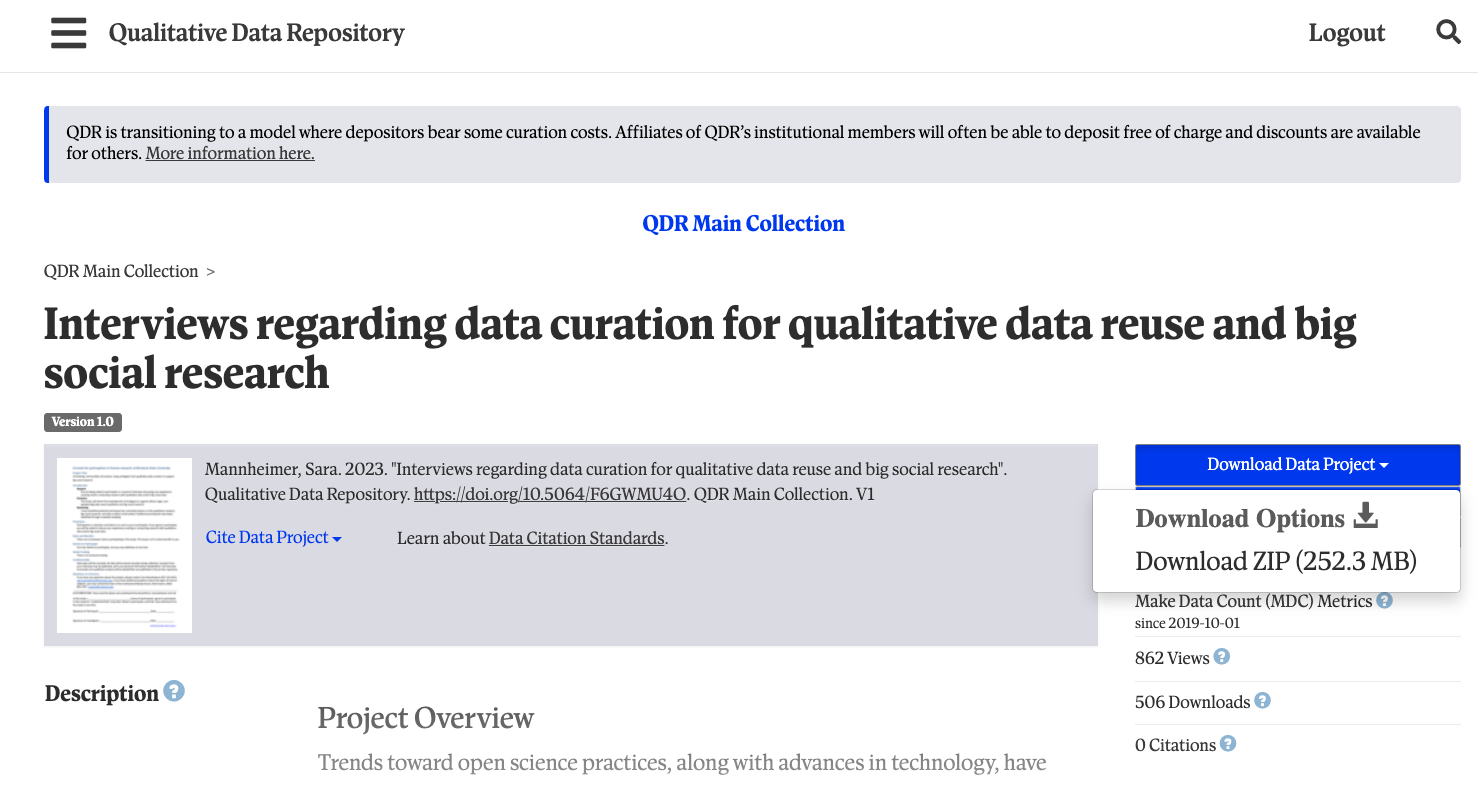

Once you have a QDR account, log in with the button on the top right

and return to the [summary page][mannheimer-qdr]. Click

Download Data Project (see image below), download the ZIP

file to your desktop, and extract the files into a folder on your

desktop.

File types

Open the folder using Finder (Mac) or

Explorer (Windows) and inspect the file extensions

(the part after the . in the filename). What types of files

are included and what software would typically be used to open them?

Don’t worry if you don’t recognize all of the file types. Just

identify what you know. If you have time during the exercise, you can

use a web search like open pdf file) to search for

information.

The project includes the following four types of files:

-

txtfiles are plain text and can be opened in any notepad or document software -

pdffiles can be opened withAdobe Readeror other document software -

nvpxfiles are NVivo for Mac projects and can only be opened in NVivo for Mac or converted in NVivo for Windows to a Windows format -

qdpxfiles are the REFI-QDA qualitative interchange format and can be opened in a variety of qualitative software

In this project, the txt files provide

metadata, or information about the project, while all other

files are part of the data itself. Taguette can’t read nvpx

or qdpx files, so the most important files to us will be

the pdf interview transcripts.

Methodologies and Instruments

Maybe you noticed something interesting about the interview topics in

the description when we first looked at the data on QDR. Let’s look

again, either on the project

page or by opening the README_Mannheimer.txt in a text

editor.

In collections of data or other multi-file downloads, there is often

a file named readme.txt or something similar. These are

meant to provide an overview of the collection and how to go about using

them.

Let’s zero in on the first paragraph under

Data Description and Collection Overview:

The data in this study was collected using semi-structured interviews that centered around specific incidents of qualitative data archiving or reuse, big social research, or data curation. The participants for the interviews were therefore drawn from three categories: researchers who have used big social data, qualitative researchers who have published or reused qualitative data, and data curators who have worked with one or both types of data. Six key issues were identified in a literature review, and were then used to structure three interview guides for the semi-structured interviews. The six issues are context, data quality and trustworthiness, data comparability, informed consent, privacy and confidentiality, and intellectual property and data ownership.

This short paragraph packs a great deal of information about the interview topics and questions. Our topic of social media privacy may share a good deal with some of the issues the original interviews focused on. Let’s look a little deeper into what we can learn to help in our own study.

Reviewing study materials

Study materials from previous studies, like interview schedules or participant observation memos, provide a window into what might work for other related studies, including both what to ask and how to approach asking. Moreover, if the research dealt with a similar study population and the final product addressed topics of interest in your study as well, it also provides some evidence that a similar study design can be effective not just in theory but in practice.

Use the information in README_Mannheimer.txt to locate

the 3 interview guides and use the readme and guides to answer the

following questions:

- Which of the six issues the researchers identified seem most relevant to planning your study? Why?

- Is one of the original study populations more relevant to understanding shared issues with your study? Which one and why?

- Read through the questions in the interview guide for the most relevant population you identified above. Are there questions that might be adapted or borrowed for your own interviews about social media privacy decisions?

For now, we’re going to focus on the Big Social Research group, because the type of data they were interviewed about their work with is the most similar to what our participants may be sharing. You may have drawn a different conclusion, and likewise, each group might provide unique insights.

If we can adapt questions and anticipate concerns and challenges relevant to our data collection, we may be able to improve the quality of our study and interview design, without repeating all the background research from the previous study.

Raw Data

Interview schedules and study plans provide insight into the research team’s expectations and approaches. The power of raw data, such as interview transcripts, is that it shows (much more directly) how the study participants construct their own views of the study topics and respond to the questions. Context and constructivism are core concerns of most qualitative researchers, leading the raw data to be possibly the most critical aspect of data for faithful and effective reuse.

That said, while it’s possible to conduct entirely secondary studies if enough raw data are available in relevant context that address relevant topics, those conditions are rarely met. Rather, raw data tends to serve as a type of pilot study - providing initial evidence as to where to begin and what to ask while still allowing the new research team to explore aspects of the data that were less relevant or highlighted in the original study.

One of the most commonly-analyzed types of raw qualitative data is interview transcripts, like we have in our project. Some tools provides support for working directly with audio and video files, but Taguette only supports text documents. Text, however, is often preferred because it simplifies the process of removing potentially identifying information and enables rapid scanning of content and accessibility technology.

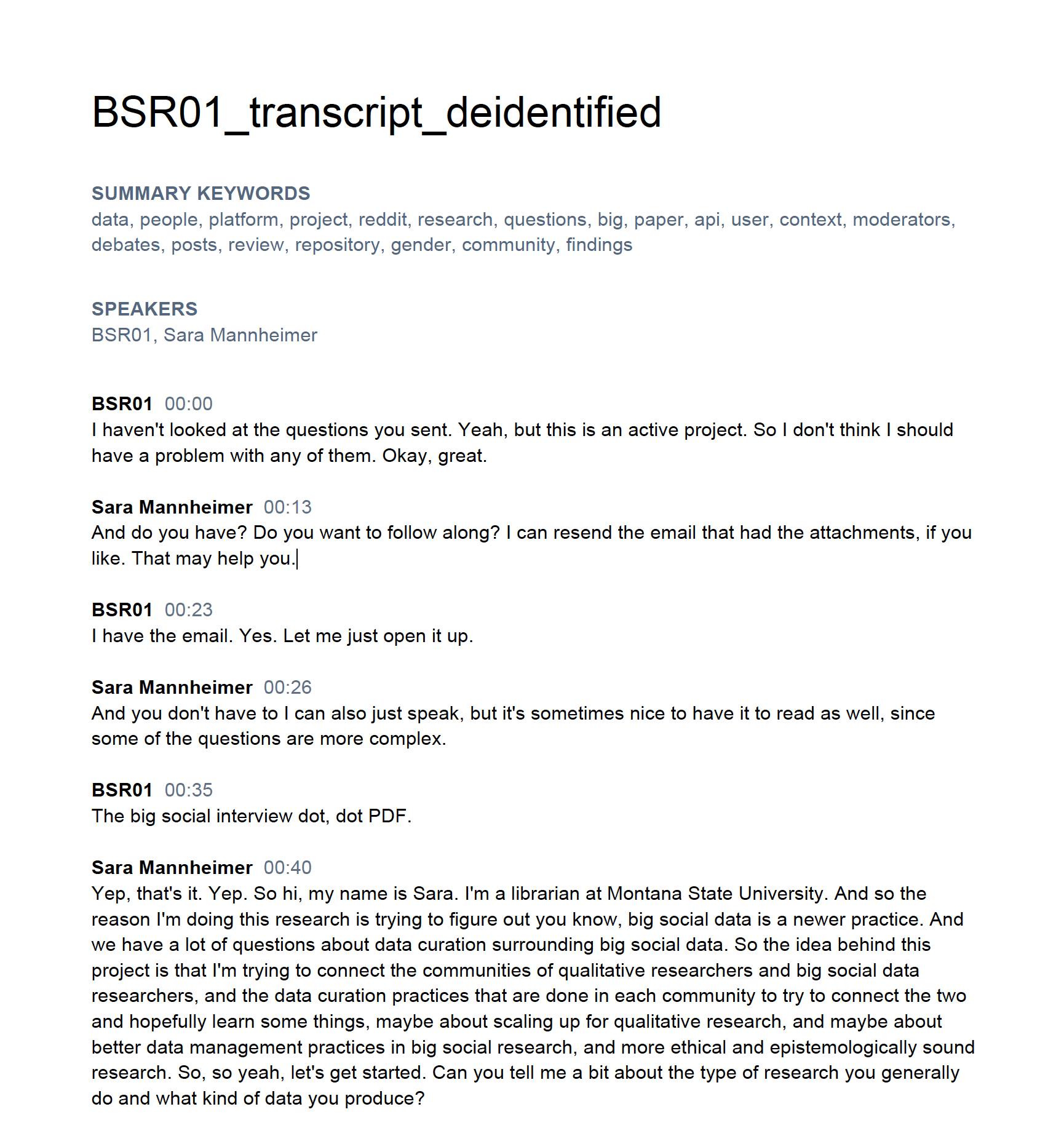

Let’s open one of the Big Social transcripts,

Mannheimer_BSR01_Transcript.pdf, in your default

pdf reader and look at how transcripts are structured in

this project.

PDF files appear as page images, but most modern PDFs

allow you to select text and other elements. In this transcript, we see

a few header elements:

- The document title

- A set of summary keywords identified by the original investigators as relevant to this interview

- A list of all speakers

After the speaker list, the transcript itself begins with each paragraph denoting a switch in speaker. The speaker’s identifier and a time stamp for the start of the conversation comprise the first line, followed by the transcribed text.

Reading even this first section in the image, we can get some insight

into decisions the research team made and how they worked. From

BSR01’s very first sentence, we see the researchers sent a

list of interview questions in advance but with mixed results:

I haven’t looked at the questions you sent. Yeah, but this is an active project. So I don’t think I should have a problem with any of them.

The respondent may not have read all the questions but did identify a project that the rest of the interview will revolve around.

Critical incident technique

Framing a qualitative interview around one specific event or project is a technique known as a Critical Incident Interview and often elicits a wider variety of reflection than abstract questions alone.

Reading interviews

Read the following excerpt from BSR01s interview and

consider the questions below:

Sara Mannheimer

All right on to privacy and confidentiality. Can you tell me about a time if any during your research process when you considered issues of privacy, protecting the data during your research or protecting the people on the platform.

BSR01 25:03

Yeah, so a good example of that would be my previous project where I was looking at biases in the language of peer review. I was looking at gender bias, what are the biases looking with gender bias. For that we had an external annotator annotate gender for the authors on the platform of these papers. And the protocol we followed was semi automatic. So we use the US Social Security data to infer genders with some confidence probability. For example, if there was a certain name, let’s say Jack, that was reported as male 99% of the time, we would tag it as male. And same thing if it was reported as female and 99% time we would tag it as female or non male rather. But if it was less confident, we had the human annotator, search for the name search for their Google profile and make a guess as to what this person’s gender is. So we were, so we were trying to mimic the reviewers perception of the author’s agenda. And because bias, the bias would be driven based on that perception, and not the self reported gender of the author. We did not release these gender annotations, because we didn’t, we thought it would cause issues if we mislabeled an author’s gender. And these authors are a part of the community that we publish. Yeah. So we opted to not release identities. And we actually at the end of the paper, we actually have an ethics statement where we talk about why we’re not doing that. But the data, the data itself is public.

Sara Mannheimer 27:08

And I guess sometimes with social media, there are like considerations of move it, like moving the data out, out of its context, in Reddit, you know, and you’re letting it be downloaded. I think in your situation, since all of the users were anonymous, that changes things a little.

BSR01 27:33

So they were anonymous in the sense that I couldn’t tie it to their real identity. But some people use this same username on all these online platforms. And that is that that is a concern. So let’s say there’s a user in my data who said something they regret, and they delete their post or their comment. It’s still going to be there in my data set.

Your study, again, is focused on the decisions individual social media users make about the privacy of their posts. This excerpt is primarily focused on how researchers protect (or fail to protect) the privacy of online users.

- What direct discussion, if any, is there of user privacy decision processes here?

- How might the example of name matching processes used by

BRS01inform how your team asks about privacy concerns with your study participants?

Key Points

- Qualitative data can take many forms, but text or transcribed audio-visual data are among the most common

- Reusing existing qualitative data can help plan studies more efficiently and effectively

- Qualitative coding and data analysis tools are each compatible with different formats of data

- The Qualitative Data Repository is a source for vetted qualitative and mixed methods data