Lesson 4: Open science hardware best practices

Last updated on 2025-06-13 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are the most popular platforms for sharing open science hardware?

- How can librarians assess if a project follows best practices?

Objectives

- Recommend platforms for finding or publishing OSH designs.

- Quickly assess a project for documentation completeness and licensing clarity.

Where do people share designs?

Open hardware designs are shared through a variety of platforms and channels, chosen depending on the project’s goals and audience.

Online code repositories such as GitHub and GitLab are among the most common spaces, offering version control, collaboration features, and easy file sharing. These repositories are the standard in software development, and will be easily accessible to some researchers but not to most of them. A good README file or website associated with the repository is necessary to ensure broad accessibility.

Some platforms like Hackaday.io or Wikifactory offer dedicated hosting for hardware designs. These are often websites where makers and scientists can showcase their work and receive feedback from peers. Specific communities, like biohacking ones, run their own Wikis. These are more accessible than repositories, but if they don’t point to them they may lack essential information (such as version control).

Academic journals also play an important role: publications such as HardwareX or the Journal of Open Hardware allow researchers to publish peer-reviewed articles that include design files and documentation. In recent years, traditional journals have started accepting open science hardware as part of their scope. This means that you may find open hardware designs for microscopy in journals such as Biomedical Optics Express.

In addition, some institutions maintain their own open access repositories, where staff and students can deposit hardware designs alongside datasets or publications. The Open Hardware Repository (OHR) at CERN is an early example of a platform where engineers and scientists share designs for scientific instruments under open licenses, making it a valuable resource for librarians seeking high-quality, peer-tested hardware documentation.

A good OSH repository makes it easy for people to upload their designs, and for others to find, understand, replicate, and contribute to the projects in it.

Checking for a good design

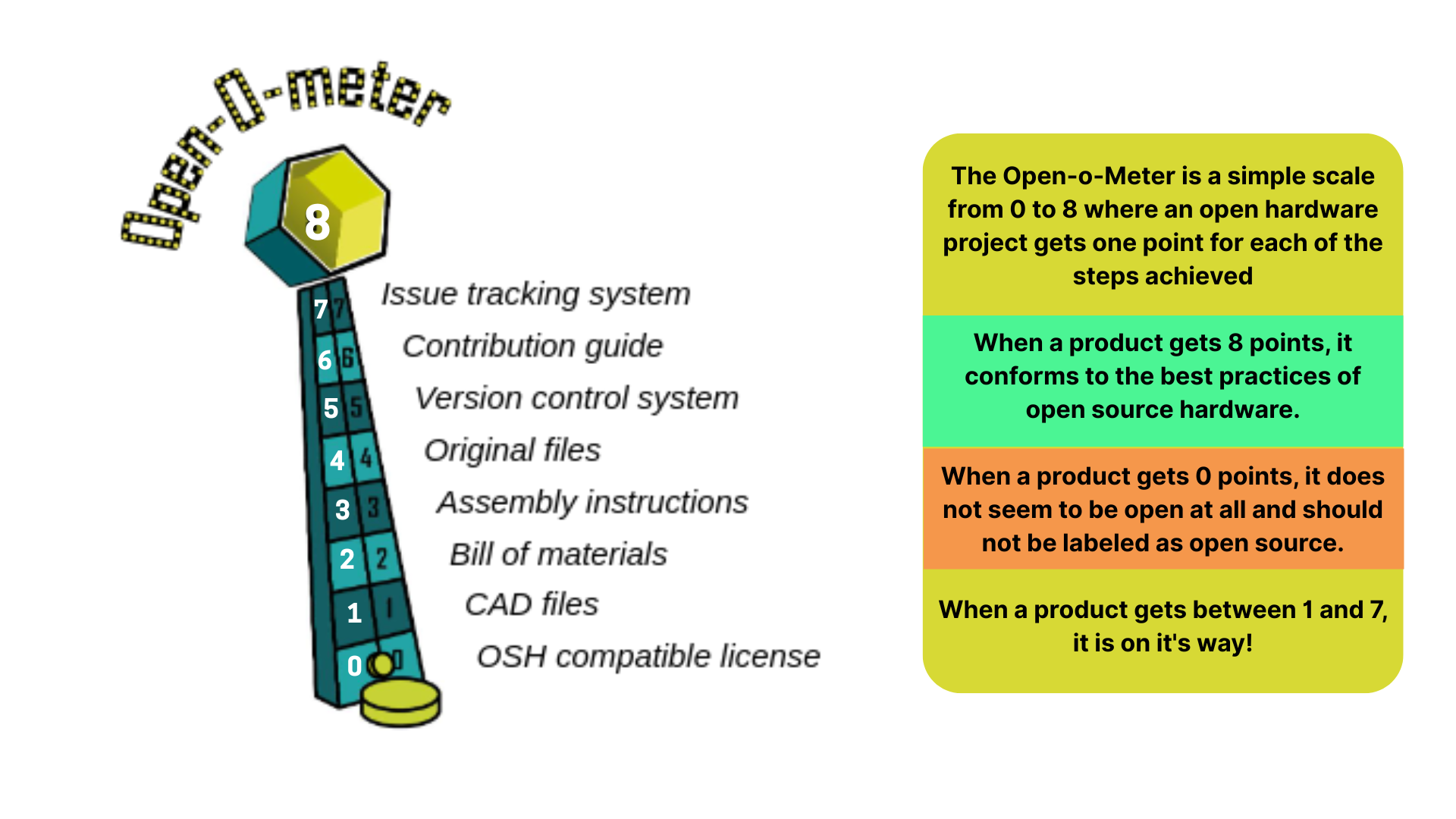

When assessing whether an open hardware project follows best practices, librarians can guide researchers by focusing on a few essential elements. The first and most critical is documentation.

A good open science hardware (OSH) project should include all the necessary files—such as design schematics, bills of materials (BOM), assembly instructions, and source code where relevant. This documentation should be clear, complete, and accessible to users who are not part of the original development team. Without it, the project may be difficult or impossible to reproduce.

Another key element is licensing. A project is not truly open unless it is accompanied by a recognized open license, such as the CERN Open Hardware Licence (OHL). This license ensures that users are legally permitted to reuse, adapt, and redistribute the design. Clear licensing also builds trust and signals a commitment to openness and collaboration.

Importantly, librarians should also consider the development stage of the design. Is the project an early-stage prototype, a more stable demonstrator, or a market-ready product? This distinction affects how usable the project is in practice.

A prototype may offer valuable insights but might not yet be fully documented or reproducible. A product-level design, on the other hand, should be well-tested, standardized, and ready for others to adopt with minimal modifications. Recognizing where a project sits along this spectrum helps manage expectations and guides the kind of support or caution librarians might offer to researchers exploring reuse.

Academics often reuse, develop and publish open hardware prototypes. This is because most use open science hardware to test new ideas, and appreciate the flexibility it provides. On the other hand, researchers can also be final users of open science hardware. In this case, they may not be interested in development, but looking for final products that ensure they are safe and reliable enough to generate good data.

Finally, signs of community engagement—such as active GitHub issues, user feedback, or visible updates—can indicate that a project is maintained and evolving. Evidence of testing or calibration data further strengthens confidence in the hardware’s reliability. And, as with any research tool, accessibility matters: designs that rely on widely available and affordable components are more likely to be usable across diverse settings. By combining these criteria, librarians can help researchers identify open hardware projects that are not only open in theory but truly usable in practice.

Challenge 1: Exploring OSH platforms

Choose one platform mentioned in the lesson (e.g., GitHub, Hackaday.io, OSF, or the Open Hardware Repository at CERN). Explore a few sample projects and assess the platform’s usability for non-expert users. Would a typical researcher at your institution be able to understand, access, and reuse projects hosted there? What guidance would you offer to someone considering sharing their own project on that platform?

Questions to ask before sharing

In addition to knowing where to find and evaluate open science hardware (OSH) projects, librarians can play a proactive role in helping researchers prepare their own designs for sharing. Before choosing a platform or writing documentation, researchers benefit from structured reflection on what they are sharing, why, and for whom.

Librarians can support this process by asking a few targeted questions that clarify the project’s goals and readiness. For example: Is the hardware functional and tested? Is the documentation complete and understandable to someone outside the lab? Does the researcher want community contributions, visibility, citations, or potential commercial uptake?

These early conversations can also surface issues that may otherwise go unnoticed, such as gaps in attribution, unclear licensing, or ethical concerns related to safety or misuse. For instance, a researcher may be unsure whether their design is eligible for open licensing, or may want to restrict certain uses without knowing how to reflect that in a license. Others may be unclear about whether internal documentation (lab notes, partial prototypes) should be included.

Readiness conversations are an opportunity to align expectations and introduce best practices from the start. If a researcher wants their design to be used by others, then thinking early about documentation structure, file formats, and accessibility will save effort down the line.

Basic recommendations such as using plain-language README files, ensuring bill of materials are clearly sourced, and publishing in open, editable formats can be helpful early on a project. Beyond discovery and curation of open science hardware, librarians can help researchers make their work not just open, but useful, transparent, and inclusive.

Challenge 2: Guiding compass

Based on the “Questions to ask before sharing” section, create a short guide or template with 4–6 key questions you could use when consulting with a researcher who wants to share an open hardware project. Your goal is to help them clarify their objectives, check for documentation completeness, and ensure their licensing approach matches their intentions.

- What is your goal in sharing this project?

- Who is your intended audience or user group?

- Is your documentation complete and easy to follow?

- Have you chosen an open license?

- Where will you publish or host the project?

- Are there any risks or responsibilities others should be aware of?

- OSH projects are shared on a range of platforms—GitHub, GitLab, Hackaday.io, Wikifactory, academic journals, and institutional repositories—all with different strengthts

- A well-documented OSH project should include at least: A README file, design files in open formats, bill of materials (BOM), assembly/testing instructions, open licensing

- Visible community engagement (e.g. GitHub issues, forum interactions, feedback) is a strong signal of project health and usability.

- Even early-stage sharing—of ideas, trade-offs, and decisions—can foster transparency, collaboration, and reuse.